|

THE WRITERS POST (ISSN: 1527-5467) VOLUME 11 NUMBER 1 JAN 2009

|

A Famous Chinese Poem Often

misunderstood By Readers AN

ARTICLE BY VU DINH DINH

VU DINH DINH was born and grew up in Vietnam. Pursuing higher education he came

to the US in 1956 and attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel

Hill, University of Chicago, and University of Hawaii where he obtained his

Ph.D. He was recipient of an East-West Center Grant, a National Endowment for

the Humanities Grant, and a National Science Foundation Honorable Mention

Award, and having served as Senior Heath Planner with the Houston Department

of Health and Human Services, taught at the college level, and had scientific

research works published in international journals. There is nothing more embarrassing than printing a poem, which was thought to have been temporarily forgotten, but found to have been a subject of active discussion among Vietnamese poetry lovers abroad. I am talking about the poem “Feng Qiao Ye Bo” (Phong Kiều Dạ Bạc) or “Anchored at Night by Maple Bridge” by Zhang Ji (Trương Kế) I introduced in the first issue of THE BRIDGE. Shortly after the release of the newsletter I received phone calls, e-mails, and letters from friends, who commented on the poem, inquired about the authorship of the translation of the poem into Vietnamese, and informed me of the existence of several articles, which had appeared in print or on electronic screen, written on the subject. Sherry Garland, an award-winning author wrote: “Thank you

for the poetry newsletter. I enjoyed reading it very much. . . There is

something about the poem that is driving me crazy though – if the moon has

set, wouldn’t that make it morning (not midnight)? Unless he (Zhang Ji) is

referring to a tiny sliver of moon. And crows are day birds, aren’t

they? I don’t think they would be cawing at midnight.” We do not know when Zhang Ji composed “Anchored at Night by Maple Bridge.” But, based on scanty information revealed in the poem such as cold weather, moon setting, difficulty to sleep in the wee hours of the morning I make an educated guess that Zhang Ji did it around two o’clock in the morning (during the Buffalo Watch), between the seventh and tenth day of November of the lunar calendar (or mid-December of the Gregorian calendar), when crescent moon was visible on a clear day. In agricultural society November is the period during which people take time off from work at the end of the harvest season to visit friends and relatives. Like Sherry Vietnamese writers not only question the unnatural behavior of crows cawing at night but also ask if the phrases “wu te” (crows cawing) and “chou mian” (sorrowful dream) simply refer to the names of two mountains nearby as some Chinese writers ascertained in the literature and painters drew them from imagi-nation. In this case these phrases should be written in capital letters as “Wu Te” and “Chou Mian.” Two Vietnamese authors Vân Trình and Hải Đà already wrote two scholarly articles in Vietnamese in response to these questions. For the benefits of English-speaking readers, I have permission to reproduce below an ela-borate, well-documented study of the subject written by Nguyễn Quảng Tuân, a Nôm specialist, who had actually gone to Suzhou to investigate the issues. * by Nguyễn Quảng Tuân Recently I had an opportunity to pay a special visit to Han Shan Temple in the city of Suzhou, China to get a better understanding of the famous poem “Feng Qiao Ye Bo” (An-chored at Night by Maple Bridge) . I wanted to see with my own eyes the landscape around the temple and gather first-hand information related to the poem in order to shed light on some controversies, which have been circulated with regards to the meanings of two ambiguous expressions in the poem, as well as to gain insight into the intended thought of this eighth century Chinese author. Han Shan Temple was built during the Liang dynasty (502-557 A.D.) and initially named Miaoli. Later, it was changed to Feng Qiao because of its proximity to Feng Bridge. Until the Tang dynasty when two zen buddhists by the name of Han Shan and Shi De came to serve in the temple as priors, the temple took the name of one of these resident monks. During the Sung period a seven-storied pagoda was added to the temple, which prompted King Song Ren Zong to give it a new name Pu Minh Chan Yuan (The All Bright Zen Court). The temple had since undergone several renovations that made the original architechtural design unrecognizable. In 1992, a five-storied pagoda was constructed to replace the old one, which at that time was already heavily damaged.

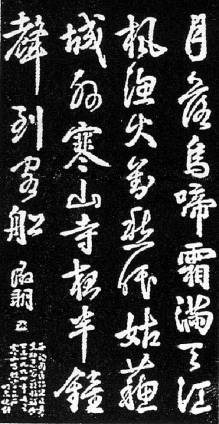

Nguyễn Quảng Tuân in front of the Comparing to other temples in the city of Suzhou in particular and in China as a whole, Han Shan Temple does not surpass them in architechtural beauty but has been made famous as a tourist attraction thanks to Zhang Ji’s poem. The poem was engraved on a stele, which still stands in the temple. Printed below is the poem in both Chinese characters and in romanized form complete with diacritical marks. This modern form of writing is called Pinyin and designed to cater mainly to Western readers. Unfortunately, because of the required labor to add diacritical marks to vowels, the other writing of Pinyin in this text does not carry tonal accents.

(A draft of the poem for engravement on stele c. 1906) This poem has been translated into English by several authors. The latest is rendered by Innes Herdan.

Moon sets, crows caw, sky is full of frost;

Verse One: One argument states that “wu ti” could be the name of a mountain or village. Therefore, it should be read as “Yue/ luo Wu Ti shuang man tian” and understood to mean “The moon sets over Wu Ti mountain/village amid a misty sky.” Thus, “Wu Ti” is no longer the cries of crows but has become a geographical name. To support this line of interpretation it is argued that at night crows do not caw. However, many researchers of Tang poetry do not accept this interpretation. They maintained that crows did caw at night, though not as common. In Chinese poetry, the expression “wu ti” can be found in Li Bai’s poem “Wu Ye Ti” (Crows Caw at Night) and in a poem by Jin Shi entitled “Zi shu” (Autobiography), in which a verse reads: “Nightly, the cries of crows are heard outside the deserted chamber.” In Vietnam, the same idea is found expressed in Quách Tấn’s poem “Hearing Crows Caw in an Autumn Evening.” The poet recalled how he came to compose it: “It was an evening of late autumn in the year Đinh Mão (1927), moonlight being dim. As I was walking home along Cồn river from An Thái wharf, I came to a deserted area where I was startled by the cries of a flock of crows. The cries were so scary, so sinister.” This experience reminded Quách Tấn of Feng Qiao wharf in Zhang Ji’s poem and he wrote: “At Feng Qiao wharf the sky is veiled with mist.” Evidently, crows are shown to have cawed at night but rarely. Furthermore, if we are to understand that the first line is to describe the moon setting over Wu Ti mountain or village, the mountain or village in question must be very far in the distant horizon and not conceivably near the wharf. For these reasons the suggested way of reading the first line as “Yue/ luo Wi Ti shuang man tian” is not logical. Reference works such as Tang Shi Zhu Jie (Tang Poetry Annotations) and Qian Jia Shi Zhu Zie (A Collection of Poems by a Thousand Poets with Annotations) did not provide such interpretation. Verse Two: The second verse has also become a subject of controversy. It is based on a statement by Mao Xian Shu of the Qing dynasty, which says: “In Suzhou across from Han Shan Temple there is a mountain called Chou Mian.” Thus, the verse “Jiang feng yu huo dui chou mian” cannot be interpreted to mean “The maple-trees along the river and the twinkling lights from fishing boats make him homesick and unable to sleep.” This line of interpretation was rejected by Zhang Wei Ming, the author of Han Shan Temple (3). He contended that since three (1st, 3rd, and 4th ) of the four verses in the poem have already been used to describe the scenery, the remaining verse (2nd) should be used to express the author’s feelings. The argument by Zhang makes sense. The two reference works I cited above concurred with Zhang’s opinion and explained the term “chou mian” to mean “sorrow causing sleeplessness.” Only in Hu Tu Qian Jia Shi (4) (An Illustrated Collection of Poems by a Thousand Poets) did Zhong Bai Jing interprete it to be the name of a mountain. The following lengthy quotation is from Zhong’s writing: “Jiang Feng is the name of the market-place. Chou Mian is the name of a mountain. Yu huo refers to the lights of fishing boats, Gu Su Cheng is the name of Suzhou city. Han Shan is the name of a temple with a famous buddha statue, yue luo wu ti means deep into the night. It was a foggy night. Lights from fishing boats in front of Jiang feng market-place twinkled across from Chu Mian mountain. Meantime, the bell from Han Shan Temple resounded as far as the poet’s boat at Feng Qiao wharf. Such was the nocturnal scenery.” I suspect that Zhong Bai Jing had never been to Han Shan Temple, thus making him come up with such misinterpretations. As a matter of fact, on one side of the temple there is only one market-place named Feng Qiao, now called Feng Qiao Street. Inside the temple there is only a hall (Han Shi Hall), where an altar dedicated to the two monks, Han Shan (5) and Shi De, is installed. Han Shan is not the name of a buddha and chou mian is not the name of some mountain nearby. During my visit to the temple and from Feng Qiao wharf next to the Grand Canal I saw no mountains in the surrounding. I heard of Ling Yan Mt., Tien Ping Mt., Tian Chi Mt., Shang Fang Mt., Deng Wei Mt., Shizi Mt., Hengshan Mt., and Heshan Mt., all of which are supposedly located far away. None of them could be detected by sight. Then, if Zhang Ji sat in his boat and looked out to view the landscape, he could only see the maple-trees, lights from the fishing boats and not Chou Mian Mt., which was not there on the other side of the river as suggested. Probably the term “shan,” which means mountain in the name Han Shan Temple (Cold Mountain Temple) misled people into believing that there must be a mountain nearby and Chinese artists, who helped to illustrate the poem, drew mountains around the temple accordingly. The photo that I took shows Feng Qiao Wharf with boats cruising in the canal, the bridge leading to Tie Ling Pass, and the Po Ming Pagoda behind Han Shan Temple. It de-monstrates the erroneous interpretation of Chinese painters whose works are often taken for granted. The facts are clear and the standard books Tang Shi San Bo

Shou (Three Hundred Poems of the Tang Dynasty) and Qian Jia Shi Zhu Zie

correctly explain the verse “Jiang feng yu huo dui chou mian” to mean “Maples

on the riverside and lights from fishing boats make me feel sad and unable to

sleep.” Verses Three and Four: “Gu su sheng wai Han Shan si,

These two lines similarly have given rise to questions because, as they said, at midnight temple bell is not ordinarily rung. However, there are on this issue several comments made by well-known Chinese writers, which are worth mentioning. Ou Yang Xiu argued that poets were usually concerned with the beauty of the verse at the expense of logical reasoning. The practice consequently resulted in a linguistic flaw. Chu Yao wrote in Tang Shi San Bo Shou Du Ben that readers of later generations for lack of anything else to say relied too much on the unlikeliness of bell sound at midnight to find fault with the poem. Ye Shao Yun in his Shi Lin Shi Hua contended that those who had never been to Wu Zhong (Suzhou) temples did not know that in those days they did ring bell at midnight. Taking into consideration these remarks, I am of the opinion that bell sound although is not commonly heard at midnight can happen on occasions when special ceremonies are conducted. For this reason poets from the Song dynasty onward who passed by Feng Qiao Wharf always remembered Zhang Ji through his description of “moon setting,” “crow cawing,” and “midnight bell.” As testimonies to the inspiration evoked by Zhang Ji’s poem I present below a collection of verses related to the subject taken from various poems by famous writers since the Song dynasty. From “Su Feng Bridge” by Lu You of Song dynasty: “Qi

nian bu dao Feng Qiao si, From “Feng Bridge” by Sun Di also of Song dynasty: “Wu

ti ye luo qiao bian si, From “Bo Chang Men” by Gu Zhong Ying of Yuan dynasty:

“Xi feng zhi zai Han Shan si, From “Feng Bridge” by Gao Kai of Ming dynasty:

“Ji du jing wo yi Zhang Ji, From “Feng Bridge” by Wen Zheng Ming of Ming dynasty: “Shui

ming ren jing jiang cheng gu, These verses prove that Chinese poets in the past recalled

the occurrence of crows cawing at night, the romantic view of moon setting

amid a cold night, and the hearing of midnight bell as something quite

natural. Zhang Ji described truthfully and vividly what happened

on that historic evening. He left behind a remarkable literary work for

us to remember and enjoy. I feel that we do not need to worry any

more about the meaning of the poem.

1. Zhang Ji (Zhang Wenchang) : Poet of the Tang Dynasty. He

was born around 756 in

2. Innes Herdan, The Three Hundred Tang Poems , new translations

illustrated by

3. Han Shan Ti: Work compiled by Zhang Wei Ming, Size: 11 x

16.5cm – 158 pages,

4. Hui Tu Qian Jia Shi (Illustrated Collection of Poems by a Thousand

Poets) Publishing

5. Han Shan: A monk poet of the Tang dynasty who lived near Qian Tai

Mt. with his fellow * On the first question I must apologize for the oversight. I do not have bias towards Hán-Việt. It is the backbone of our literature. Our language would not have been as rich and versatile as it is today without Hán-Việt. I did have the version on hand when I typed the newsletter. But, after working with the Chinese version, the Pinyin version, the Vietnamese translation, and three different English translat-ions I totally forgot about the Hán-Việt version. Or, perhaps Alzheimer has unknowingly been creeping in. As a matter of fact, from conversations with my friends, verbally or via Internet, I was surprised to discover that they remembered Zhang Ji’s poem through the Hán-Việt title “Phong Kiều Dạ Bạc.” Nobody ever mentioned to me the title in present-day Vietnamese. Perhaps the translation into “Đêm Đậu Thuyền Ở Bến Phong Kiều” was too long to be acceptable and the Hán-Việt title was expressive enough to relate to the poem. Furthermore, some of my friends could quote the poem for me in Hán-Việt without hesitation. This shows how deeply Vietnamese appreciate the poem although it is not in their own language. So, here is the Hán-Việt version of the poem: Phong Kiều Dạ Bạc Nguyệt lạc ô đề sương mãn

thiên, As to the authorship of the translation of this poem into present-day Vietnamese I relied on an article by Nguyễn Quảng Tuân printed in Tản Đà Toàn Tập (Complete Works of Tản Đà). He pointed out that the error was committed when Trần Trọng San attributed the translation to Tản Đà in his book Thơ Đường (Tang Poetry), Part I, published in Saigon in 1957. Later on the mistake was perpetuated by Lý Văn Hùng in his book Việt Nam Văn Chương Trích Diễm (Vietnamese Selected Literary Works) published in Chợ Lớn in 1961. The version that they printed reads as follows: Trăng tà tiếng quạ kêu sương, This is the version that most of us remember. However, as early as 1942 Đẩu Tiếp Nguyễn Văn Đề already printed a translation of the poem in his book Trong 99 Chóp Núi (Among 99 Mountain Tops) published by Tân Việt in Hanoi, in which he attributed the authorship to Nguyễn Hàm Ninh (1808-1867), a contemporary of Cao Bá Quát. Tản Đà was born much later after these nineteeth century poets. Nguyễn Hàm Ninh’s versions reads: Đêm Đậu Thuyền Ở Bến Phong Kiều Quạ kêu, trăng lặn, trời

sương, Apparently, the original translation by Nguyễn Hàm

Ninh had been modified and was attributed to Tản Đà. It is

to be noted that the earliest collection of Tản Đà works Tản

Đà Văn Vận did not have this translated poem. Other publications

simply listed the author of the translation as unknown. VU DINH DINH The Writers Post &

literature-in-translation, founded 1999,

based in the US. Copyright © Vu Dinh Dinh & The Writers Post 2009. Nothing in this magazine may be downloaded, distributed, or reproduced without the permission of the author/ translator/ artist/ The Writers Post/ and Wordbridge magazine. Creating links to place The Writers Post or any of its pages within other framesets or in other documents is copyright violation, and is not permitted. |